Tag: Caste Equality Project

Spring Updates from Saptari District

NYF’s long-term Caste Equality Project (CEP) is our most ambitious and daring undertaking yet. Our goal is to empower Dalit communities in Nepal to access the opportunities and resources they need to build towards the futures they envision for themselves and their children.

In order to meet these goals, NYF launched two phases of the Caste Equality Project. Phase I was the Educating Dalit Lawyers (EDL) initiative, which we launched in the summer of 2022. (You can read more about EDL here). Phase II of the Caste Equality Project takes place in Saptari District. The project is led by NYF’s very own Lalit Gahatraj, and it officially launched in the summer of 2023. We’re anticipating the work in this phase to be a decades-long project in order for us to truly build a transformative and sustainable movement.

Almost a year into the launch of the project in Saptari District, we’re thrilled to share some exciting updates!

Education Advocacy

At the end of April, NYF officially launched the School Enrollment Campaign for students in Saptari District in Tirhut Rural Municipality. In collaboration with the local government, NYF set into motion a vibrant initiative aimed at boosting school enrollment in the region. Our dedicated team, alongside enthusiastic students and teachers, began spreading the word across communities with energizing rallies and personalized home visits to promote the value of education.

On May 3rd, NYF kicked off the campaign by taking to the streets. Community members and students made posters and marched through their communities while chanting inspirational slogans like, “Send all children to school/leave no one behind!” & “Quality education is our right!”

Our team also made door-to-door visits to encourage parents to enroll their children in school. At the same time, they addressed concerns and answered any questions parents may have.

Then, in mid-May, NYF distributed hundreds of school uniforms and bags to children in the region. These uniforms were handmade by our industrial tailoring students enrolled at Olgapuri Vocational School. You can read more about this unique, cross-program detail in a recent blog post, here.

The School Enrollment Campaign ran until May 10th. Lalit Gahatraj, CEP Coordinator, shared that the early signs are very promising, with an uptick in school attendance already noted! This surge is partly attributed to the community buzz around NYF’s scholarships and nutritious mid-day meal programs, which are drawing more and more families to enroll their children into school.

Peer Counseling Program

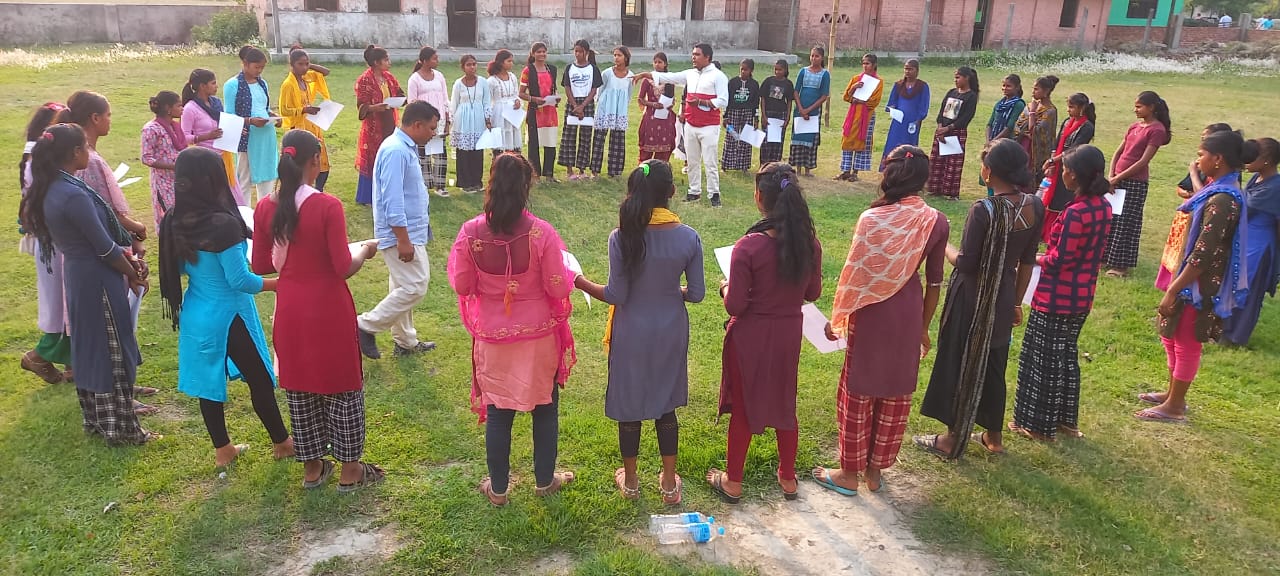

In mid-April, thirty girls (aged 13 to 19) from the rural municipality of Tirhut in Saptari District, traveled with our staff to Olgapuri Village to participate in a five-day Peer Counseling training at our very own Ankur Counseling Center. The training began April 23rd.

For many of these girls, it was their first time leaving their village, a journey that brought both excitement and apprehension. Our staff dedicated a lot of time to earn and maintain their trust while supporting them every step of the way.

Building peer counseling skills within individuals will help empower young leaders to make an impact in their own communities. This is a prime example of NYF’s approach to addressing the “felt needs” of communities over “observed needs,” which includes recognizing community members as experts of their own experiences, successes, and challenges. This community-centered approach is a cornerstone of NYF’s strategy to ensure sustainable, far-reaching social change!

We’re excited to see the impact this peer counseling program will have on the wider Dalit community.

Engage with this update on Facebook or Instagram.

Street Drama Campaigns

In February 2024, over 100 people gathered to watch ten girls from Tirhut Rural Municipality, Saptari District, perform their first street drama. Their play tackles various scenarios related to child marriage. This included dowry negotiations by the groom’s family and self-serving middlemen, the squandering of dowry funds on alcohol, a daughter’s stand against her forced marriage, and harmful consequences for girls experiencing early marriage.

The audience, including men, women, children, and elders, responded positively. During a guided discussion following the play, one man observed, “We often engage in certain practices without fully comprehending the consequences. This play was an effective eye-opener.”

New Community Centers in Saptari District

Construction begins with a groundbreaking ceremony

In early April, NYF hosted a groundbreaking ceremony for the construction of two new community centers in Saptari District. The ceremony was completed in collaboration with village members, and a respected elder named Chebli Sada performed a “jag puja,” or foundation blessing, to purify the land. The blessing was an important start to the construction of the ceremony because it allowed a connection to the spirits of the land and the ancestral deities of the people we’re serving. She also led a prayer to ensure a smooth progression of construction, free from hindrances and misfortune. Offerings of sweets, betel nuts, betel leaves, and incense were buried beneath the foundation, symbolizing a blessed new beginning.

Since the ceremony, construction on the two community centers have been underway, with a tentative completion date for June.

Community Centers will serve as vital hubs for Caste Equality Project programs

These two community centers in Saptari District will house most of our programs in the Caste Equality Project, holding spaces for education, childcare, and other important initiatives like:

- Adult literacy classes (reading, home finance, legal literacy)

- Town meetings where teachers, parents, and local leaders build community-wide, unified strategies

- Nutrition-focused home cooking classes for mothers, applying NRH principles

- Disaster preparedness programs

- Peer counseling

- Women’s empowerment and co-op groups

- Teacher training

The plan is to hire staff for the centers from within the communities served, to build sustainable local capacity. Each center (and we hope to build more!) aids NYF’s sustainability in Saptari District, expands and enhances regional impact, and resources NYF to pursue its vision for meaningful change for the communities served. The more centers we fund, the more strongly we can scale while maintaining existing momentum.

The enthusiasm from the community in response has been heartwarming. We’ve seen widespread eagerness to engage, a testament to the importance of community involvement in bringing sustainable changes. Our late founder Olga Murray’s vision is alive and well, manifesting visibly in the strides we are making in Saptari District.

These initial campaigns have been made possible by several generous friends in the NYF Community. But we still need wider support to continue our work within (and beyond) the Caste Equality Project. Please click here to make a donation if you’re able to!

Industrial Tailoring Students Provide Support for the Caste Equality Project

Former Kamlaris enrolled at Olgapuri Vocational School make school uniforms for massive back-to-school initiative!

Through the Caste Equality Project, NYF has spent the last few months working with local families, teachers, and stakeholders to organize a massive push towards educational equity in Saptari District.

Saptari District is a remote area of southeastern Nepal. Casteism, systemic neglect, and other generational challenges have left families unable to leverage their incredible potential to build prosperity. Boldly encouraging and championing the launch of the Caste Equality Project was among the last major projects of our late founder, Olga Murray’s lifetime, and she has trusted the NYF staff and community to share her promise and see this work through the end. Our goal is to empower Nepali Dalit communities to access the opportunities and resources they need to build towards the futures they envision for themselves and their children.

Our work in Saptari District will equip the community to be the primary agents within this important movement—exactly how Olga would have done it.

With the new school year in the district beginning at the end of April, we are stocking school kitchens with fresh, high-quality, nutrient-rich ingredients to combat widespread malnutrition and encourage school attendance. A huge part of this effort includes providing hundreds of children with school uniforms.

But these aren’t just any uniforms. They’re actually being crafted by NYF’s very own students currently enrolled in Olgapuri Vocational School’s Industrial Tailoring program. This program offers more than just hands on vocational training—but also an empowered path to a new life.

From Vision to Reality: The Industrial Tailoring Course

NYF’s Industrial Tailoring course at Olgapuri Vocational School represents a story of a worthwhile transformation from one collective vision. The idea originated from a women’s empowerment group within the Freed Kamlaris Development Forum (FKDF). FKDF is a community-based nonprofit led by and developed specifically for former kamlaris—young Tharu women who were once trapped in a system of indentured servitude in the homes of Nepal’s elite. (You can read more about NYF’s 20-year-long project freeing kamlari girls and abolishing the practice here!)

During a group discussion, these women saw the need for professional training in industrial tailoring. They recognized the potential for a stable, flexible, and lucrative career in Nepal’s booming clothing export industry. Their request was so powerful and enthusiastic that our team had to find a way to provide this opportunity. In May 2021, we welcomed our first class of students in the new Industrial Tailoring class.

Industrial Tailoring quickly became Olgapuri Vocational School’s most popular courses for women. It’s not just about learning a valuable trade; it’s about creating opportunities, building empowerment, and reclaiming futures. These special training courses support these women in their journeys to advocate for a better future for themselves, their families, and their communities.

Industrial Tailoring and the Pursuit of Caste Equality Today

In 2024, NYF’s Industrial Tailoring course continues to be a very popular option for women, including many former kamlaris.

We’re thrilled to share that the talented students currently enrolled in the course are supporting NYF’s efforts to advance educational equity in Saptari District by helping to create the much-needed school uniforms! Students are practicing their new skills by lovingly preparing structured shirts, jackets, skirts, slacks, and neckties for boys and girls in a variety of sizes—all while receiving an additional income!

Graduates of the Industrial Tailoring program have been supporting the process by fine-tuning the final products created by their peers. These graduates are earning a higher rate than they would at the factories they work for! The assignment is perfect for refining important tailoring skills that they’ll need in their new careers, while also earning a living wage through this special project. They’re creating a total of 670 sets of uniforms for the children in Saptari District to wear on the first day of school.

A Transformative Change in Saptari District

The timing of this educational push through the Caste Equality Project lined up perfectly with the industrial tailoring course. It has created a unique and lucrative opportunity for former kamlaris to support in creating these long-lasting school uniforms. We’re delighted that these women—who were once robbed of educational opportunities and their childhoods—are now empowered leaders who can support and transform communities in Nepal through projects like this.

As NYF continues to grow, our team molds and develops programs in the contexts of local need, potential, and participation. We strive to ensure our interventions in Nepali communities are done through sustainable measures that emphasize self-sufficiency whenever possible. What a golden example!

Join us in celebrating these resilient women who are leading the way to a better tomorrow. You too can support the Caste Equality Project and this educational push by making a donation today.

2023 Impact Stories: Thank you!

(Above, Caste Equality Project in April 2023) – NYF nurse Radhika Sapkota dispenses multivitamins for children who have completed their check-ups at the Nutrition Outreach Camp. No one in 7-year-old Esha’s* household can read, so Radhika explains the dosage in a bit more detail to Esha’s mother. As she does so, she makes some simplified marks on the vitamin box to help her remember the instructions.

2023 Reflections & Highlights

As we begin the new year, our global team is deeply grateful for everything we accomplished with your support last year:

- In February 2023, NYF celebrated the 25th anniversary of the opening of our flagship Nutritional Rehabilitation Home.

- Our first 16 Educating Dalit Lawyers scholarship recipients officially entered law school. They are impressing their professors with their passion and dedication to the law.

- Over the summer, our nutrition team helped launch the Caste Equality Project in Saptari District. They provided nutritional outreach and care to over 5,000 children and their caregivers.

- In July, Ankur Counseling Center launched a Community Mental Health program to nurture mental wellness and empower individuals to recover from mental health crises.

- Our Kinship Care program is now providing enriched care to keep girls in school, lowering the risk of child marriage.

- We expanded the mission of our New Life Center to offer services to children visiting Kathmandu for critical medical services.

- And thanks to careful observations and learnings from our work during the COVID-19 pandemic, we re-envisioned our Olgapuri Vocational School “satellite” trainings. They are now more impactful than ever in upgrading the standard of living in rural villages.

The above are just a handful of highlights from our work in 2023. And while we’re proud of these accomplishments, we know that the real impact NYF makes are shown in the individuals we work with. So on that note… we wanted to compile and share some of our favorite stories from 2023!

We hope these stories showcase NYF’s love, care, and commitment for the youth and families we work with. We also hope you feel proud of the impact we are making together every day.

Kriti*

Scholarships for Students with Disabilities

Seven-year-old Kriti* loves puzzles, picture books, and making new friends. But because schools equipped for students with intellectual or developmental disabilities are rare in Nepal, Kriti (who has Down syndrome) has spent most of her life at home, unable to attend classes like the other children she likes to play with.

NYF has offered Scholarships for Students with Disabilities for over 30 years, but until now, these scholarships were limited to students with physical disabilities, like deafness or mobility challenges. This was due to the limited number of safe schools for students like Kriti.

NYF is so pleased that this has changed in recent years. Our team of social workers have assessed several Kathmandu Valley schools for students with special intellectual or developmental needs. Three of these schools have inspired our team’s confidence enough that we have opened the Scholarships for Students with Disabilities

scholarship program to include students living with intellectual disabilities. In 2023, we welcomed 23 such children into this scholarship category!

Our social workers have made valuable connections within these schools, allowing for open dialogue about each student’s needs. NYF is also engaged with the parents of these children, who are tremendously relieved to know that resources are available to help families like theirs provide safe, loving, encouraging educational care for their children.

“NYF … has a philosophy of ‘working themselves out of a job’. Truly unique among NGOs, NYF will choose a mission, will create solutions and then hand off the new model to local people to run. This is not only a very respectful and sustainable model, but it also frees up the organization so they can tackle the next challenge.”

— Sheila, Supporter

Chandra*

Kinship Care

Grandpa, or Hajurba Kumar, is raising Chandra, 14, whose father died in an accident many years ago. Chandra’s mother remarried soon thereafter. Her new husband’s family refused to accept her son into their family, since he was not part of their paternal line.

Chandra’s grandparents stepped in to provide the little boy with a stable home. This allowed their daughter, Chandra’s mother, the opportunity to build a more stable life for herself as well, in a social context that is often extremely challenging for single mothers without the education to support a good-paying career.

Today, Hajurba Kumar, now widowed, is raising Chandra. Chandra is Hajurba Kumar’s pride and joy. The loving, supportive connection between them is warm and strong. This has provided Chandra with a wonderful foundation as he enters his teenage years.

An NYF Kinship Care stipend has kept this family together as Hajurba Kumar ages. Your support is allowing them to prioritize Chandra’s education without worrying about the money required to keep this growing young man properly fed as he enters his voracious teenage years!

Chandra is currently thriving in the 8th grade. He routinely scores in the top five students of his class. He has a great future ahead of him, and we are so grateful to you for making it possible.

“Taking on herculean tasks, NYF has tackled Nepal’s biggest obstacles and continues to drive change. So many lives have been impacted as a result of this work.”

— Andrew, Supporter

Bhagwati*

New Life Center

Bhagwati*, 34, lost her husband several years ago. His death revealed a secret that would drastically impact her life, and the lives of her two young children. He had been living with HIV, and, fearing the devastating social stigma of this diagnosis, had not disclosed his status to anyone, not even Bhagwati.

Soon after his death, Bhagwati began experiencing frightening symptoms of her own. “Weight loss, persistent cough, and difficulty breathing became a part of my daily struggle,” she says. “I visited the hospital, and when the doctors saw the seriousness of my condition, I was referred to a special hospital in Kathmandu.”

In early 2023, Bhagwati was diagnosed with HIV. To her dismay, her youngest son was also found to be living with the virus. She felt as though her entire life was crashing down around her.

When Bhagwati’s health had stabilized enough for a transfer, the hospital referred her and her son to the New Life Center. There, she would learn techniques for managing her son’s health, as well as her own.

“Our stay at the NLC proved transformative,” Bhagwati says. “Our care was all-encompassing—nutritional meals, essential medications, crucial lab tests, and, most importantly, counselling services to address our emotional well-being. We were discharged after a three-month stay, armed with medicine and a newfound resource when we need it the most.

“Since then, we have been taking our antiretroviral treatment regimen. The journey hasn’t been without its challenges, but we’re not alone. The project staff that had become our pillars of support during our time at the NLC continue to stand by us. Whenever hurdles arise, they’re there, offering guidance and a helping hand.”

(To protect Bhagwati’s privacy, this illustration was created by AI based on photos from the NLC.)

“As a donor, I have been involved with Nepal Youth Foundation for over 15 years and have supported a young girl’s education from high school all the way through medical school. She has become a successful surgeon and is making a contribution to the Nepalese society.”

— Yat-Ping, Donor & Volunteer

Nisha*

College Scholarship Program

Nisha* was raised in NYF’s care, so our team was deeply proud to witness her receiving her diploma from one of Nepal’s top universities this year!

A bright student with a sparkling presence, Nisha has dreamed of a career in the media for a long time. Her new degree in Media Studies from the School of Arts at Kathmandu University (and her stellar GPA) have already landed her a job in the media department at a travel company, where she’ll gain excellent on-the-job experience.

Someday, Nisha hopes to team up with other young media professionals to make a big difference for communities across Nepal. Thank you for helping Nisha, and many other young people like her, access the education that opens these remarkable opportunities!

We are thrilled to be supporting NYF for such outstanding work they are doing to improve the quality of lives of children in Nepal through education.

— Sunita, Supporter

Pooja*

Vocational Training & Career Counseling (SAAET Project)

Pooja*, 33, lives with her husband, mother-in-law, and three children. She can’t remember ever having attended school, though she can read Nepali if given enough time to focus. Her family doesn’t have much, relying primarily on daily income her husband earns from taking on daily labor jobs. Pooja had to ask him for money for every basic expense. This caused a great deal of friction in the relationship.

For this reason, Pooja aspired to have an income of her own, to support her children and family and to fulfill her own needs as well. She learned about the SAAET Project from her local women’s co-op group and took part in the October 2022 session.

She constructed her first greenhouse quickly after completing the training session. By late January 2023, she had already sold an entire crop of cauliflower. Encouraged by this success, she added a second greenhouse, where she planted peas and green beans. By spring, Pooja was handling basic household expenses on her own—which transformed her previously-tense relationships with her husband and mother-in-law.

Pooja’s husband realized if he helped with the greenhouses, he could bring in more money for the family than his daily labor did. In strong partnership, he has joined Pooja’s endeavor, and they are now investing some of the year’s profits in a third greenhouse.

“The DH Ross Foundation has made a number of grants to NYF over the last 20 years. We have been consistently impressed by their work providing a range of educational and health and nutrition services to children and youth, and are glad to support their vocational training and health outreach work.”

— Ken, Partnering Organization

Mina* and Rupa*

Olgapuri Children’s Village

In February 2023, a temporary shelter home referred sisters Mina*, 4, and Rupa*, 3, to Olgapuri Children’s Village.

Mina and Rupa are very close, and very bright. They’re now both attending kindergarten and doing quite well. When they were found by the original shelter, they were determinedly caring for each other the best way they knew how, having been failed by all of the adults in their lives. Our team is thrilled that their days of fending for themselves are over. These sisters deserve a normal, healthy, nurturing childhood—and that’s exactly what they’ll receive at Olgapuri Children’s Village.

Mina and Rupa’s parents married against the wishes of their mother’s family. Their father belonged to a Dalit caste (formerly known as “untouchable”). As a result, their maternal grandparents rejected the entire family.

Family life proved too much of a struggle for the girls’ father, who abandoned the family during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soon thereafter, their mother (who was still rejected by her parents) remarried and started a new life in India with her new husband, leaving her children behind. Even then, Mina and Rupa’s maternal grandparents refused to take them in or even acknowledge them, due to their caste status.

Mina was born with a hearing challenge, and when she arrived at Olgapuri, she was unable to hear or speak. She also hadn’t been exposed to Nepali Sign Language, though she and her younger sister Rupa made good use of a “home sign” language that they developed together organically.

We are amazed at the progress the girls have made. Mina, who is skilled at lipreading, eagerly devoted herself to learning to write in her special-needs kindergarten class. She was awarded first place in her class for handwriting, bringing home a prize of several notebooks, new pencils, pencil sharpeners, and good-quality erasers! The children and house parents at Olgapuri quickly learned how to communicate with her, and they have surrounded her with warmth, kindness, attention, love, support, and safety.

Thanks to a special medical grant from a committed donor, Mina received a cochlear implant over the summer, which is allowing her to hear for the first time. She’s picking up new skills very rapidly and now attends school in the main classroom.

Meanwhile, Rupa—who at age 3 is already her sister’s fiercest advocate—no longer needs to help her sister navigate the world safely. Rupa is enjoying her classes, as well as opportunities to play with other children. She is making connections and relaxing into the stable rhythm of Olgapuri life. She’s experiencing holistic security for the very first time. The girls now have a large, loving family of healthy, attentive adults to meet their needs. And older siblings with ample time and attention to share!

We support NYF because the programs are community-based/grassroots, carried out by Nepali staff (who understand local needs) and are focused on education and health, especially for the benefit of children and young adults.

— Ann, Supporter

Rajendra*

Educating Dalit Lawyers

Rajendra* is from Doti District, a hilly region in far western Nepal. He grew up in a home shared with his parents, two brothers, one sister, and his grandmother.

Overt casteist violence and discrimination were a common occurrence in his hometown. But he also witnessed his neighbors pushing back. Once, he recalls, local police refused to act against a group of casteist young adults who were making a campaign of harassing and abusing Dalit people in the area. Local Dalit families bypassed the local authorities and lodged a case with the district level police. The perpetrators were held accountable and charged a penalty!

Watching this case unfold in real time provided great insight to Rajendra about legal terms and procedures, the importance of law and justice—and ways the law could transform conditions for families and communities like his.

Rajendra was honored to earn an EDL scholarship. He was even more excited when he learned he’d won a seat at National Law College in Kathmandu, one of the best schools in Nepal.

A year into the program, Rajendra is thoroughly enjoying the learning environment at the college. He’s impressed with the quality of the teachers here, and with their teaching methods. When he identifies areas of weakness in his own skill levels, he immediately begins strategizing ways to improve.

Rajendra is tremendously grateful for the Educating Dalit Lawyers scholarship opportunity. He’s looking forward to defending the rights of his community as a fully-fledged lawyer!

“NYF is addressing important big-picture issues in Nepal without losing touch with the individuals they are serving. “

— Anonymous, Donor

Shanta*

Caste Equality Project, Nutrition Outreach Camps, Vocational Training and Career Counseling

Shanta*, 23, attended one of NYF’s April Nutrition Outreach Camps in Saptari District with her 2-year-old son, Amar. She was very grateful for the opportunity to have her precious son seen by a pediatrician. And she was relieved that NYF was working with local health workers she knew and trusted. Shanta and her family are from the Madhesi Dalit subcaste, so opportunities like these are very rare.

The pediatrician diagnosed Amar with mild malnutrition, but Amar was in otherwise good health. There was no need to refer him to an NRH. Instead, Shanta and Amar sat down with NYF’s nutritionists to discuss practical, affordable strategies to improve the boy’s nutrition at home. During this discussion, Shanta shared details about her background. She had only attended school long enough to write her name and cannot read or write.

She married at age 19. Her husband spends most of the year performing backbreaking migrant labor in Saudi Arabia. Shanta is raising Amar on her own, and she is also responsible for caring for her aging in-laws.

Sending Shanta’s husband and his brother for work in Saudi Arabia was very expensive, and the family incurred a great deal of debt to do so, all in the hopes that the effort would result in better financial stability moving forward. Unfortunately, the investment hasn’t paid off, and Shanta misses her husband terribly.

Shanta has tried to grow wheat and other crops on the tiny plot of land she shares with her in-laws, but the meager earnings from this have never been enough to sustain the family. She frequently goes without meals to ensure her son and her in-laws can eat.

NYF’s Nutrition team made thorough notes during this discussion, and during nutritional counseling sessions with other families. When they returned to Kathmandu Valley, they had a list of early suggestions for Lalit Gahatraj, the CEP Coordinator. Shanta’s story was similar to those shared by many other families. The team suggested that running one of our “Tea & Snacks Shop” trainings in the area would be an impactful start for some of the families we had met.

When NYF announced that they would run an experimental session to assess the effectiveness of these businesses in the region, Shanta signed up eagerly. She completed the training in June 2023. She received her food cart, cooking tools, and other start-up support, and launched her new street food business.

During the first few days, she was already making a profit of 500 rupees per day. This is roughly on par with Nepal’s minimum wage. On big farmer’s market days, she brought in double the money. Amar comes along with his mother and enjoys “quality testing” each batch of snacks. He’s also enjoying a greater variety of fresh vegetables, which Shanta purchases in the markets she works in.

Shanta has quickly developed a sense of her clientele’s preferences, and she is bringing in more income with each month. Her success has been transformative. Soon, she hopes to call her husband back home to Nepal so they can expand this new business and live together as a family. She is confident that together, they can bring in just as much income—if not more—than the wages he is earning in Saudi Arabia.

Support from friends like you make these transformations possible. As we move through 2024, we’re looking forward to the possibilities of the life-affirming transformations in store for the children we serve. Thank you, and dhanyabad!

Meet the Saptari District Moms helping to launch the Caste Equality Project

In April 2023, Radhika* (29) joined thousands of families who brought children to a Nutrition Outreach Camp in Saptari District. Her children, Kamala* (13), Dinesh* (10), and Sharmila* (7) had never seen a doctor.

Radhika was anxious at first. Members of Dalit castes, historically labeled as “untouchable” across South Asia, still face tremendous systemic discrimination, exploitation, and societal exclusion. Would they be turned away, or ignored, or even threatened or beaten?

She was relieved when the NYF team told her their organization wanted to help as many Dalit families as possible.

Clockwise from top left: Radhika, Kamala, Dinesh, and Sharmila welcome the NRH fieldwork team into their home for a follow-up visit in Sept. 2023.

While the NRH visit significantly improved their nutritional status, systemic challenges related to caste identity have made that progress difficult to maintain back home.

NYF is helping them and other moms in Saptari District overcome these challenges and achieve lasting health. Meanwhile, their feedback is helping us ensure that the Caste Equality Project is as successful as possible.

Then the pediatrician told Radhika that all three kids were malnourished—Dinesh and Sharmila severely so. She felt a jolt of helplessness, and even shame. But NYF’s team immediately invited the whole family to the Kathmandu Nutritional Rehabilitation Home (NRH) for treatment. Radhika was stunned that the three-week stay would be free-of-charge.

At the NRH, Radhika’s kids quickly gained weight and became healthier. And Radhika mastered the nutrition lessons, even encouraging her kids to participate. At discharge, the family was cautiously optimistic about applying everything they’d learned and continuing their progress.

But when the NRH fieldwork team followed up in September 2023, Radhika had run into significant challenges. Dinesh and Sharmila had started growth spurts. Even though they hadn’t lost weight, they were both technically malnourished again. Once more, Radhika felt guilt and overwhelm. But the NYF team reassured her. Her story highlights unique problems facing the Dalit community. Understanding her challenges is helping NYF create solutions.

Six months after Sharmila left the NRH, NYF’s Field Supervisor, Ramesh Pant, weighs her to check progress. The family & field team worked together to create a dry, level surface to do so.

Caste discrimination prevents many Dalit families from building sturdy, permanent homes. As our Educating Dalit Lawyers scholars gain experience, they will help families navigate the legal hurdles standing between them & safe, dignified living spaces.

In the meantime, our team is honored to be invited inside these homes. This simple respect helps strengthen the message that no one is untouchable.

Photo credit: Naresh Tuladhar

| Learning from Radhika | Project Solutions |

|---|

| Improved nutrition kicks off important growth spurts. While Radhika is using all the best techniques she learned at the NRH, her growing kids need more food to sustain healthy development than she can afford. | ➤ | Creating a nutrient-rich school lunch program ensures growing kids eat at least one well-rounded meal per day, lowering the financial burden for parents right away. |

| Radhika had children very young without access to family planning knowledge. Feeding multiple “big kids” is more difficult than feeding individual “little kids.” | ➤ | An awareness campaign on child marriage & the dangers of early, rapid childbearing will empower women to marry later & control family size. |

| Radhika makes ends meet by selling milk from their family cow. Ideally, the kids would drink this milk, but they cannot afford to lose this income. | ➤ | Income-generating trainings & small business start-up funds for parents will help them afford the ingredients for a balanced diet. |

| Radhika’s husband is a migrant laborer overseas. She and her children rarely see him. He sends as much money home as he can, but the whole family still relies on daily wages from labor done on local farms. | ➤ | Vocational trainings for young adults provide lucrative alternatives to migrant labor, keep families together, and help parents make enough money to keep their kids in school. |

| Radhika’s family has been denied citizenship rights due to a lack of formal records, so she can’t buy or lease land for a garden. The nearest market with fresh produce is too far away and too expensive. | ➤ | NYF is exploring options to lease land near villages for large community gardens where local women can grow produce for their families and sell excess to their neighbors! |

| Because she can’t own land, Radhika’s house isn’t permanent. Clean water & hygienic facilities are limited. Even when care is taken, water contamination leads to illness, causing rapid nutrient loss. Malnourished children are especially vulnerable to infection. | ➤ | Improving community access to clean water will involve installing plumbing in central areas, raising awareness about water purification & creating a local water management team. |

Bina* is one of the best-educated people in her village: she completed grade 10 with excellent scores. She brought her sweet one-year-old daughter Padma* to the same camp Radhika’s family attended. Padma was severely malnourished and needed urgent care at the Kathmandu Valley NRH.

While at the NRH, Bina was surprised to learn how cooking methods impact the nutritional value of food. She felt dismayed that in all her efforts in school, no one had ever taught her any of the nutritional information that would have helped her nourish her baby. Now she knew her usual cooking methods often wasted crucial nutrients. She had even been cutting away and discarding the most nutritious bits!

At follow-up in Sept. 2023 (at left), Bina shared that she is applying her updated knowledge every day. Padma’s health is better than ever. Bina’s health is better, too. Vegetables are hard to access in Bina’s village—she has to walk an hour to get to the market. But Padma’s health is worth the trip. Bina has wrapped this errand into her regular routine, and she’s sharing tips with her neighbors, too!

The Caste Equality Project is NYF’s most ambitious initiative yet. We’re vowing to empower Nepal’s Dalit communities

—starting right here in Saptari District.

Saptari District Moms like Radhika are helping shape this project!

Nepal Youth Foundation launches Phase II of Caste Equality Project!

We are beyond excited to share that earlier this month, NYF officially launched Phase II of the Caste Equality Project (CEP) in Saptari District! (For more information and updates about Phase 1: Educating Dalit Lawyers, click here.)

Saptari District is a region of Nepal where Dalit populations (those historically called “untouchable”) face particularly complex barriers between themselves and crucial resources like education, good nutrition, safe shelter, and more. NYF is finally beginning the work of turning the tide for children living in Saptari District, bringing 30+ years of expertise—and the promise of longevity!

Watch our launch video on YouTube:

Phase II will bring specialized versions of our existing, proven programming into the Musahar Dalit villages of Saptari District. We’ll also be working with 2-3 villages first before gradually expanding to reach more. Over a generation (or more!), NYF will work to empower these communities to break cycles of inequity and foster community-led growth and achievement—just like we did with the Tharu communities in western Nepal between 2000-2020†.

† In early 2000, NYF learned of the practice of kamlari bondage, in which young girls from the Tharu ethnic minority were being sold into kitchen slavery by their fathers. This was happening due to systemic oppression of their communities, including patterns of predatory lending, which were making this practice necessary for family survival. During the next 20 years, NYF embedded a team in the regions impacted by this practice, intervening on behalf of the girls and providing the community supports needed to obliterate the practice legally, in actual fact, and even on the level of community acceptance. Click here to learn more about this remarkable success.

Between the summers of 2023-2024, NYF has plans in Saptari to:

- Drastically improve the daily midday meal in schools, using learnings from our Community Nutrition Kitchens during our earthquake response and our COVID-19 response. The meal will meet each growing child’s core nutritional needs. This will improve school attendance and will improve the nutritional status of the children themselves.

- Organize town meetings to help teachers, local government officials, and parents create a joint, cooperative strategy where K-12 education is concerned.

- Establish a safe “study hall” environment as a space for preschoolers (all day) and older children (after school) to receive educational support, allowing parents to focus more on working without worrying about childcare.

- Provide vocational training for 20 young adults in construction trades like plumbing, electrical, welding, and carpentry. These young adults will then return to their villages to begin their first trade jobs: improving the school buildings back home!

- Bring school infrastructure to usable standards, including bathroom improvements, safety, and more.

- Establish a local co-op/savings group among the women, beginning by providing livelihood training and business start-up support to 20 mothers.

- Begin establishing a peer counseling program.

- Launch a large-scale awareness and prevention campaign about topics related to women’s health: menstrual hygiene, early marriage, nutritional health, and the traditional dowry system, for example.

- Hold adult literacy classes.

- Organize disaster preparedness programs and establish emergency response resources within the villages themselves, including forming an action group for disaster response, plus environmental protection and hygiene (for example, protecting water safety).

Pictured above: Sunita Rimal, NYF’s Nutrition Coordinator, with a community health worker in Saptari District during a nutrition outreach camp earlier in 2023.

How you can help:

Our team on the ground in Saptari District will pay strict attention to the successes and pain points of each of these programs, always ready to adjust where needed. But for our programs to have lasting, sustainable effect, NYF needs strong support from friends who know the power of healthcare and education in the lives of children, families, and communities!

Staff Spotlight: Lalit Gahatraj

Eighteen years ago, when Lalit Gahatraj was still in school for social service, he signed up for a volunteer teaching opportunity for kids in western Nepal who had limited access to K-10 education.

When he arrived in the area he would be serving, he faced a disappointing reality. Many parents refused to send their children to Lalit’s classes when they learned he was part of the Dalit community. “I went to them to help their kids,” he says. “But they would not accept me as a teacher.”

Soon thereafter, at age 18 and still working through school in evening classes, he joined the NYF team as a field worker for the Nutritional Rehabilitation Home. He’s been with NYF ever since, developing his career through a series of positions.

Now he’s about to begin the tough work of leading the Caste Equality Project: Phase II launch in Saptari District.

Lalit, now 36, grew up on a farm in Dhankuta District, a hilly region of eastern Nepal (north of Saptari). He is still one of the only people from his village’s Dalit population to have completed college. He’s also the only one who has earned a master’s degree (he focused his studies on anthropology). Lalit is very excited to be playing a role in creating programming especially for the Dalit community.

“The people are facing many problems in Nepal, especially the Dalit,” he says. “I’ve had a chance to get a good education. I want to do something for my society.”

He’s bringing tremendous insight to the role, both professionally and personally. Though the practice has been formally outlawed since the 1960s, Lalit grew up experiencing “untouchability.” As a child, he was part of a particularly strong soccer team that competed in a tournament away from his village. Higher-caste teammates were invited to sleep inside the homes of other competitors. “But they didn’t allow me to enter their house because they knew I’m from the Dalit community,” he explains. He couldn’t touch water or food intended for the whole group, either. If he did, higher-caste people would refuse to eat or even touch it again.

Despite this, Lalit felt more impacted by discrimination when he arrived in Kathmandu for college. Finding a room to rent was an unexpected challenge. The first question—his full name—always announced his caste status (Nepali surnames are linked to caste). Even though he could prove he was able to afford the rent, landlords refused to rent to him once they learned his caste. “It hit me a lot,” he says. “I thought that Kathmandu is a city area, with civilized, more educated people living here. But the thinking is traditional.”

Lalit’s time with NYF has been a much better experience.

From the beginning, NYF has worked to ensure casteism had no place in its hiring practices. Leadership had also always cultivated a culture of respect and warmth among staff members. Lalit has always felt like family on the NYF team. “When I joined NYF, I was just 18. I never thought I would work here so long, in the same organization. But the work culture prevalent in this organization and the programs run by NYF are directly connected to the core of my feelings. I’ve learned so many things here. Olga, she’s amazing. I’ve been impressed by her contribution to the Nepali children for a long time. Som, Raju, our whole team is a very good team for humanitarian work in Nepal. So I’m lucky I’m here.”

Lalit’s strong role managing NYF’s Earthquake Response

For Lalit’s first 11 years at NYF, he stayed with the Nutrition team in various capacities. Then, in 2015, the Gorkha earthquake hit. In the immediate aftermath, Lalit became the In-Charge for the humanitarian assistance NYF offered to those injured in the disaster. Four months later, when it became clear how long earthquake recovery would last, he was placed in charge of NYF’s relief work in Sindhupalchowk District. This was one of the worst affected areas, high in the treacherous Himalayas.

Here, for almost 18 months, Lalit oversaw a complex array of projects: safe housing for displaced children; the establishment of ten Community Nutrition Kitchens in community schools; a daycare-style program allowing parents of young children to focus their energy on rebuilding while their kids were under the watchful care of trustworthy, loving educators. Lalit also managed a campaign that brought running water to villages whose natural springs—their only water source—had been destroyed or shifted by the earthquake.

“Finally and most importantly,” he says, “we reconstructed 51 community schools, building 225 rooms in five districts.”

During this time, Lalit and his team lived among those they were serving, in rough conditions with very few amenities. Lalit led the project team, managed reporting and admin, navigated government red tape, handled logistics for construction projects, and coordinated community members, political leaders, local NGOs, and others to ensure each project supported the recovery of the communities as smoothly as possible. The project was very difficult at times. But Lalit is proud of the ways it allowed his leadership skills to blossom.

When he returned to Kathmandu in 2017, Lalit’s success in Sindupalchowk earned him a promotion to NYF Operations Manager. He’s been handling operations and logistics on a day-to-day basis since then, with his skills stretched and strengthened again during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Spearheading the Caste Equality Project

Lalit is eager for his newest challenge, and is preparing to relocate his family (himself, his wife, and their two children) to a village in Saptari District where he says the conditions are even worse than those he grew up with.

He’s especially enthusiastic about the improvements planned for educational resources in the area. Many members of the Dalit community aren’t even aware of the rights they are guaranteed under Nepali law. “They are deprived from the fundamental right,” Lalit says, “and human rights. So the education is very powerful.”

“Education is a very, very powerful thing to avoid discrimination,” he explains. “If the children get a good chance for better education, and they’re able to find a good job, they can earn good money. And if they have good money, they can build their nice house, they can send their children for good school, they can easily fulfill their basic needs. So education is very, very important.”

It’s an ambitious vision.

Even now, Lalit is still encountering the cruelty of casteism in his own life. When he recently returned to his home village for his mother’s funeral, local Brahmin priests outright refused to carry out her last rituals because of her caste, leaving the family to manage the heartrending services on their own. Denied the profoundly human comforts of shared grief and spiritual community during this difficult time, Lalit describes this indignity as one of the most painful of his life. After living so far from home for so long, he had not realized casteism was still so alive—so open and so ugly—back home.

But the experience spurs him forward in his hopes for Saptari District, where the situation is such that a family’s “main focus is to work for survival rather than to send the children to school.” These communities have been so neglected by the society around them, and even by other well-meaning NGOs, that they are hesitant to trust the hopeful promises of outsiders who may not understand the realities they face each day.

But Lalit, with his existence as part of the Dalit community himself, is optimistic. “Sometimes I ignore which caste I belong to,” he says. “I’m a human being. I have to do some good work for society, for the people.”

Higher-caste parents don’t often refuse to allow Lalit to help their children these days. But some still comment on his caste when they hear his full name, generally with surprise at the level of education he’s managed to attain.

In Saptari District, the tone is different, with Dalit community members reacting with admiration. There’s a big difference between knowing that a Dalit child can attend college and meeting a Dalit man who has actually done it—and is now using that education to empower the community.

“I’m always thinking in a positive way. So, [my Dalit identity] makes me stronger, to be a good example for my Dalit society.”

Lalit’s first order of business in Saptari District will be to establish trusting connections within the community. “My main role is coordinating the people and the government authority, because without their help, we cannot do anything. So I’ll live with the community. I’ll visit the school day-to-day and monitor the school. What is the education system? Why are the children not going to school? What are the factors? I’ll try to find them.”

We’ll be sharing more about the Caste Equality Project (CEP) at this year’s hybrid Founder’s Day celebration on June 1st. If you haven’t registered already, please click here!

Educating Dalit Lawyers Update: Students have started school!

Thank you to everyone in the NYF Community for generously supporting the launch of Phase 1 of the Caste Equality Project—Educating Dalit Lawyers!

We are proud to announce that our first group of 15 Educating Dalit Lawyers (EDL) scholarship recipients started classes on Monday, February 27th, 2023.

About the Students & the Law Schools

Our EDL students are attending the top three law campuses in Nepal, each affiliated with Tribhuvan University. Specifically, five students are attending Nepal Law Campus in Kathmandu (the best, most competitive law school in Nepal). Five are attending National Law College in Kathmandu, and five are attending Prithvi Narayan Campus in Pokhara. These colleges offer excellent human rights law courses.

This year, a total of 1,152 prospective law students earned a passing score on the rigorous entrance exam. The Tribuhuvan University-affiliated law campuses only offer 280 seats per year, which go to the highest scorers. Our students have worked tremendously hard for their places in law school. We are honored to be supporting their goals of providing much-needed legal services to their communities!

Student Profiles

Two of our students are from the Madhesi subcaste (often identified as the most oppressed of the Dalits), with three other subcastes also represented. We have students from all seven of Nepal’s provinces: Lumbini (5), Madhesh (3), Bagmati (1), Sudurpashchim (2), Province-1 (1), Gandaki (2), & Karnali (1).

Nine of the students are brand new law students, and six had already begun law school before we began offering our scholarship. Of these six, two are in their second semester, three are in their third semester, and one is in his fifth semester.

Ten of our students are men and five are women. This was a surprising outcome, because two-thirds of our original group were women. The nuanced challenges facing Dalit women is just one of the areas we are determined to understand better in the coming years.

Ravi*

Ravi comes from Nepal’s eastern plains region, where Dalit families often have limited job opportunities due to illegal untouchability practices. Growing up, he witnessed tremendous injustices towards Dalit people within his own village, including accusations of witchcraft and humiliating public punishments.

After his brother married a young woman from a higher-caste family, their home original village expelled Ravi’s family. The woman’s relatives filed a legal case accusing Ravi’s brother of human trafficking. Their family went into debt combatting this unjust charge, and Ravi became keenly aware of how little access they had to legal support. Having no one to turn to for guidance during this time was terrifying for the entire family.

Now Ravi hopes to become a public prosecutor focused on safeguarding the rights and interests of the Dalit community.

He is thrilled to be receiving the Educating Dalit Lawyers scholarship and living in a shared EDL apartment near campus. “Living together with other friends from this group is fun, and it has also helped me in my studies. We discuss various issues and topics, which enhances our understanding and clarity,” says Ravi.

Sushma*

Sushma grew up facing the especially unjust treatment Dalit women experience every day. Her childhood was full of horrifying instances of violence against women and girls from her community. This unfortunately includes personal experiences which she has only just begun to share with anyone.

This mistreatment by all parts of society caused Sushma to doubt her own worth. She grew up feeling isolated and never truly safe.

In school, Sushma learned about Nepal’s constitutional provisions regarding the rights of Dalits and women. But she knew first-hand that violations were being suffered every day. She hopes to specialize in criminal law, ensuring these rights are honored by Nepal’s legal system and making society safer for future generations.

Being surrounded by other EDL scholars has already given Sushma a new sense of safety and purpose. When Sushma put on her formal uniform for the first day of college, she says, “I felt an amazing sense of accomplishment, as if I had already become a lawyer. This opportunity is extremely valuable and I want to utilize this to do my best.”

*Names changed to protect the privacy of our students.

Next Steps

Our scholarship team is working with Dignity Initiative to refine our application and selection process for the next group. We expect to be launching our next call for applications in our Educating Dalit Lawyers program in June 2023!

We are also preparing to launch K-12 educational programs in the Dalit communities living in eastern Nepal’s Saptari District—the groups of Dalits facing some of the worst multifaceted, complex forms of discrimination, including massive educational neglect.

Our team is exited to share more about these new programs in the coming months.

Dhanyabad!

Visiting Nepal as NYF’s new U.S. Executive Director

Written by Ryan Walls, U.S. Executive Director, regarding his recent two-week trip to Nepal to visit our Nepal Country Office, programs, and NYF staff. Above photo by Sanjoj Maharjan.

Namasté from Nepal! Last month, I took a trip to Nepal for the first time in nearly 20 years. This time, I was there to spend time with Som, Olga, and the rest of the NYF family.

I first visited Nepal in 2001 as a wide-eyed 20-year-old student. My program was grounded in anthropology and from day one we were immersed in Nepali language and lived with local families in Kathmandu. My Newari host family lived on what was then the western edge of Kathmandu’s urban sprawl beneath Buddha’s benevolent eyes atop Swayambunath Stupa. We studied Nepali and engaged in discussions and lectures on Nepali history, ethnic groups, economic development, environmental issues, women’s rights, and more.

Although Kathmandu has changed in many ways since my first visit, the essence of the city remains, along with the kindness and gentle curiosity of its people. The scents and smells were as I remember – a heady mix of wood smoke, incense, and car exhaust. The intricate choreography of the ceaseless street traffic is also the same.

Little shrines still pepper the city, often where you least expect them. Kathmandu is filled with homages to religious deities from grand to tiny and barely perceptible. One morning my taxi swerved around a small offering plate in the middle of a busy intersection and it reminded me of how faith pervades many parts of life there.

The most noticeable change is the sheer density of Kathmandu. I vividly recall my first entrance to the city in 2001. After landing at Tribhuvan International, we were whisked away to Pharping, a village in the hills of the southern valley rim for an orientation. Days later, we trekked into Kathmandu, traversing the edges of expansive dayglow green rice terraces. Many of these same terraced fields are now filled with housing for the capital’s burgeoning population.

The auto rickshaws, a thrilling way to explore the city 20 years ago, are long gone, now replaced with more scooters and motorbikes than I remember.

Olgapuri Children’s Village

I spent several days at Olgapuri Children’s Village and the NYF offices during my Nepal trip, getting to witness the magic that Som and his smart, caring team create.

Olgapuri, in many ways, strikes me as a self-sustaining ecosystem. Each moving part supports the others. The staff cultivate a safe, nurturing environment where the children thrive and grow. The industrial tailoring students craft clothing for the children at Olgapuri and the Nutritional Rehabilitation Home. The vocational students make furniture for the residential homes, the community center, and the NYF offices. The gardens produce organic vegetables that nourish the children and the staff. The cows offer up their fresh milk while their manure returns to the crops as rich fertilizer. And, of course, the children infuse the community with a vibrant undercurrent of life and love. It’s a perfectly balanced system.

I engaged in deep conversations with the Nepal NYF staff who manage and lead the education programs, the scholarships, the vocational training programs, the counseling center, and the finance and accounting department. I now have a more nuanced understanding of how each program fits into the broader holistic NYF model. It’s difficult to fully understand the sophistication of these programs without seeing them in person. The genius of NYF really is in this multi-layered, systematic approach to breaking the cycle of poverty by empowering Nepali children to fulfill their dreams.

Trip to Saptari District in Nepal

During my second week, Raju Dhamala, NYF’s Nepal Executive Director, and I flew to the southeastern city of Biratnagar. We were to visit the villages where NYF will launch the Caste Equality Project, our most ambitious project to date. We met with local leaders and teachers, spoke with parents and children, and visited schools. The villagers are part of the Musahar caste, the lowest of the Dalit sub castes. They’re barred from owning land and therefore cannot even grow their own food.

The schools are in poor shape with crumbling, cracked walls. They’re vulnerable to heavy rain, wind, and any hot or cold weather. Snakes and other animals crawl into classrooms while school is in session. There are two or three usable classrooms in each village but they have limited student capacity. Other classrooms sit vacant, falling apart and lacking doors or sometimes even ceilings. The teachers we met often received only a three day orientation before being thrown into classrooms that combine two or three grades into one. Attendance rates are low – typically less than 15% of children in this community go to school.

Despite innumerable challenges, Som and his team have devised thoughtful objectives and strategies for addressing these inequities. This summer, NYF will launch a comprehensive program, compiling the best practices our Nepal team has developed over the years in education, nutrition, vocational training, mental health counseling, community development, and other areas, to uplift the entire socio-economic status of these communities.